Christianity has long shaped the world’s cultural, artistic, and architectural landscape. From humble beginnings to the towering cathedrals that dominate skylines, Christian architecture reflects a deep connection between spirituality and design. Whether through intricate stained glass windows or the soaring arches of Gothic cathedrals, the structures that house Christian worship tell a story of devotion, power, and the human desire to reach toward the divine.

But what exactly defines Christian architecture? Is it the grandeur of the building or the symbolism embedded in every corner? Over centuries, Christian architects and builders have developed a distinct vocabulary of design that integrates religious symbolism with regional styles. This evolution has resulted in a rich tapestry of architectural styles, from the early basilicas and Romanesque churches to the Gothic masterpieces and modern, minimalist chapels.

The Early Days: Foundations of Christian Architecture

“For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I among them.” – Matthew 18:20

In the early days of Christianity, worship often took place in homes or secret locations due to persecution. With the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire after 313 AD, the need for formal places of worship grew. Early churches, known as basilicas, were inspired by Roman civic architecture, featuring long central aisles and semi-circular apses. Though simple, these structures laid the foundation for Christian architecture, emphasizing function and community while symbolically representing the journey toward salvation.

As the faith expanded, Catholic architecture began to take on symbolic meaning. The basilica’s long nave represented the path of the faithful, and the raised altar symbolized heaven. These designs fostered unity, bringing the congregation together in a shared space of prayer and devotion. Though not yet ornate, these early churches embodied the spiritual essence of Christianity and created a new form of sacred space.

As Christianity spread beyond Rome, local influences began to shape church design. In the Byzantine Empire, centralized plans and domes became popular, symbolizing the heavens. These innovations would pave the way for further developments in Christian and Catholic architecture, as sacred spaces began to reflect both religious beliefs and regional styles.

The Rise of Cathedrals: Romanesque Christian Architecture

The 11th and 12th centuries marked a significant shift in Christian architecture as Europe emerged from the Dark Ages and began to experience a resurgence in building. This era gave rise to the Romanesque style, which became the dominant form of church construction throughout Western Europe. Romanesque architecture is defined by its solid, massive quality, with thick walls, rounded arches, sturdy piers, large towers, and decorative arcading. These buildings exuded a sense of permanence and strength, symbolizing the power and endurance of the Christian faith.

One of the key characteristics of Romanesque Christian architecture was the development of large stone cathedrals that often featured barrel vaults and groin vaults to support the heavy roofs. The interiors, though dimly lit by small windows, evoked a sense of mystery and reverence, drawing the faithful into a spiritual experience that was as much about the architecture as the liturgy. Churches such as St. Sernin in Toulouse and Speyer Cathedral in Germany are prime examples of Romanesque architecture, with their imposing facades and expansive interiors designed to inspire awe.

As Romanesque cathedrals flourished across Europe, they set the stage for even more ambitious architectural advancements, leading to the development of the Gothic style.

The Gothic Era: Reaching Toward Heaven in Christian Architecture

“The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands.” – Psalm 19:1

As the Romanesque period gave way to the 12th century, Christian architecture evolved into the soaring heights and intricate designs of the Gothic style. Characterized by pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, Gothic cathedrals were designed to inspire awe and lift the gaze heavenward. These architectural innovations allowed for taller, more open structures, enabling large stained glass windows to fill the interiors with divine light, which was seen as a representation of God’s presence. This period produced some of the most iconic cathedrals in history, such as Notre-Dame de Paris, Chartres Cathedral, and Canterbury Cathedral.

Gothic architecture also placed a heavy emphasis on verticality and light, with spires and towers reaching toward the heavens. The interiors were designed to feel expansive yet intimate, guiding the worshiper’s eyes upward in a symbolic gesture of connecting the earthly with the divine. Lavish decorations, intricate carvings, and religious iconography were common throughout these buildings, reinforcing their sacred purpose and the deep connection between faith and art. The Gothic era pushed the boundaries of engineering and aesthetics, leaving behind a legacy of magnificent cathedrals that continue to inspire awe and reverence.

Renaissance Revival: The Rebirth of Classical Christian Architecture

The Renaissance era, beginning in the 15th century, marked a return to classical principles of balance, harmony, and proportion in Christian architecture. This period sought inspiration from ancient Roman and Greek architecture, reviving classical orders, columns, domes, and symmetrical layouts. Unlike the verticality of Gothic churches, Renaissance architects emphasized symmetry and clarity, embodying the Renaissance ideals of reason and humanism. Churches such as St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City stand as masterpieces of this period, blending religious significance with classical grandeur.

During the Renaissance, architects like Bramante, Michelangelo, and Bernini contributed to shaping monumental churches that reflected both the authority of the Church and the artistic revolution of the time. The use of large domes, such as the one atop St. Peter’s Basilica, became a defining feature of Renaissance church design. These domes symbolized the heavens and brought a sense of unity to the architectural space, representing the cosmos. This period reinvigorated Christian architecture by merging the sacred with the secular, resulting in structures that expressed both spiritual and artistic ideals with grace and precision.

Baroque and Rococo: Ornate Christian Architecture in the 17th and 18th Centuries

The Baroque era, emerging in the 17th century, brought an entirely new level of drama and grandeur to Christian architecture. Baroque churches were characterized by their bold, dynamic designs, intricate details, and lavish use of materials such as gold, marble, and frescoes. This style aimed to evoke emotion and awe, reflecting the Church’s power and authority during the Counter-Reformation. St. Peter’s Basilica’s interior and Rome’s Church of the Gesù are iconic examples, where rich decorations and sweeping curves immerse worshipers in a theatrical experience of faith.

Rococo, an extension of the Baroque style in the 18th century, further emphasized opulence but with a lighter, more playful touch. Rococo church architecture featured elaborate stucco work, delicate ornamentation, and pastel colors. Churches like the Wieskirche in Germany exemplify this style, with intricate ceilings and ornate altarpieces designed to convey divine beauty. These designs, though extravagant, maintained the spiritual connection, using architecture to create an immersive space where worship felt almost otherworldly, filled with grace and splendor.

Colonial and Missionary Influence: Christian Architecture Across the Continents

As European powers expanded across the globe during the Age of Exploration, Christian architecture began to spread to the Americas, Africa, and Asia through colonialism and missionary efforts. Missionaries brought with them the architectural styles of their homelands, leading to the construction of churches that blended European design elements with local materials and cultural influences. In Latin America, for instance, the influence of Spanish Baroque architecture is evident in churches like the Cathedral of Mexico City, which combines native artistry with European forms.

In Africa and Asia, missionaries often adapted their designs to local climates and available resources, resulting in unique hybrids of European and indigenous styles. These mission churches and chapels were not only places of worship but also symbols of European dominance and the spread of Christianity. In some regions, these buildings incorporated local motifs and craftsmanship, creating a distinctive blend of cultures. The lasting legacy of this architectural exchange can still be seen today in colonial-era churches across continents, where faith, culture, and architecture intertwined in fascinating ways.

Modern Christian Architecture: Balancing Tradition and Innovation

In recent decades, Christian architecture has taken a turn toward modernism, often leaving behind the grandeur and symbolism that once defined sacred spaces. Instead of inspiring awe with soaring ceilings and intricate detail, many contemporary churches now embrace minimalism, favoring stark concrete walls, angular designs, and glass facades. While this shift is often framed as innovative, it sometimes feels as though the spiritual heart of these structures has been sacrificed in the name of modern trends. Ronchamp Chapel by Le Corbusier, for example, is praised for its unconventional shape, but for some, it lacks the reverence and soul that more traditional churches evoke.

Though some modern churches try to incorporate traditional elements like stained glass or cruciform layouts, the results can feel more like a nod to the past than a true continuation of it. Many contemporary churches prioritize functionality and sustainability over the transcendent beauty that once defined Christian architecture

Global Diversity in Christian Architecture: A Cultural Reflection

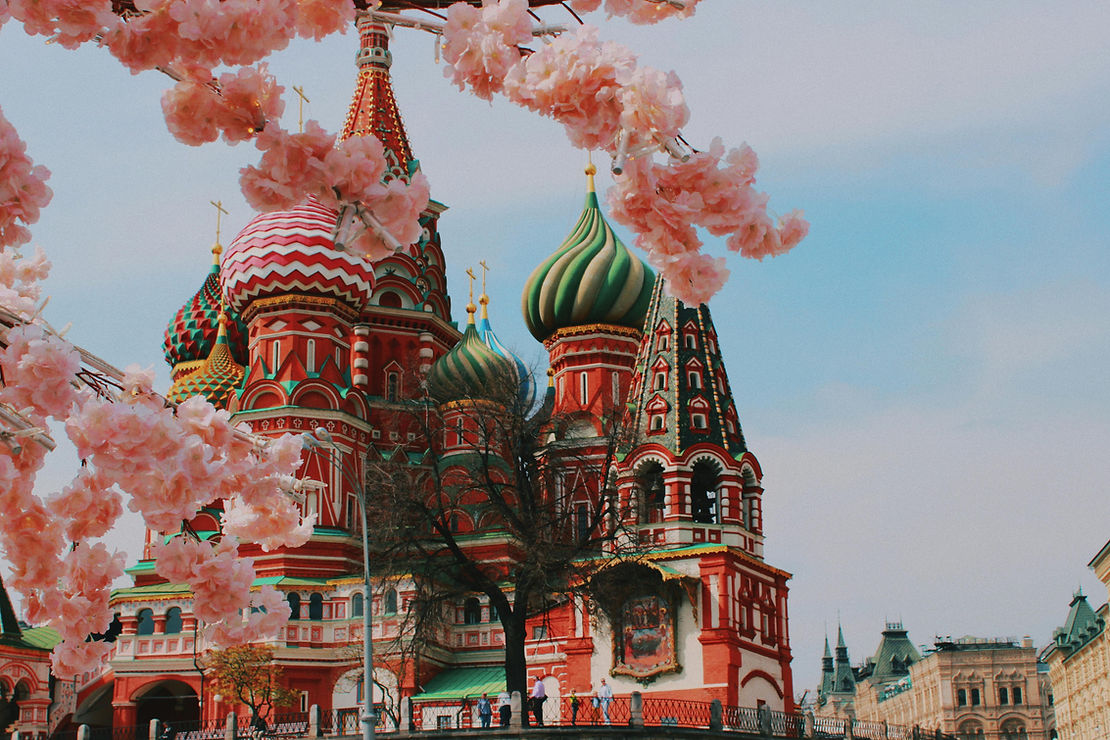

One of the most fascinating aspects of Christian architecture is its incredible diversity across the globe. As Christianity spread, it was shaped by the cultures, materials, and traditions of the regions it touched. In the Eastern Orthodox world, for instance, Byzantine churches became known for their domes, mosaics, and iconography. These structures, with their richly decorated interiors and distinctive layouts, were designed to reflect the glory of heaven and serve as a visual representation of faith. Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, originally a Byzantine cathedral, remains one of the most iconic examples of this tradition.

In contrast, other regions, such as Latin America and Africa, reflect a fusion of European colonial styles with local influences. Churches in Mexico or Brazil might feature Baroque elements brought by Spanish and Portuguese missionaries but are often adorned with indigenous motifs and craftsmanship, creating a unique blend of Christian architecture that resonates deeply with local culture. Similarly, in Africa, some churches incorporate local building techniques, like mud-brick walls or thatched roofs, while still adhering to Christian symbols and structures.

Conclusion: From Cathedrals to Chapels – The Living Legacy of Christian Architecture

From the towering Gothic cathedrals of medieval Europe to the simple, modern chapels of today, Christian architecture has continuously evolved, reflecting changes in theology, culture, and art. Each era has left its mark, with some periods embracing grandeur and ornamentation, while others have turned toward simplicity and functionality. Despite these shifts, the core mission of Christian architecture remains: to create spaces that foster worship, inspire faith, and reflect the Lord.

While opinions on the direction of modern church design may vary, the living legacy of Christian architecture is undeniable. It is a testament to the enduring power of faith to shape the built environment and to adapt to the needs of each generation. Whether through the intricate carvings of a Gothic cathedral or the minimalism of a contemporary chapel, these structures continue to serve as places of gathering, reflection, and spiritual connection. And in this, their legacy lives on, bridging the gap between tradition and innovation, past and future.

Recent Posts

15 Floor Plan Graphic Styles That Will Elevate Your Presentation Game

The Role of Shadows in Architectural Storytelling

When Furniture Becomes Architecture: Blurring the Line